Games as Storytelling

I consider games to be an immensely powerful vehicle for storytelling, because they have something no other medium has - player input.

In a way, this means that the player always has a say in the game’s narrative. Even if the story is completely linear, the player is required to take a series of steps in order to reach a conclusion. This can take any form, be it completing levels in a platformer or picking dialogue options in an RPG. Not only does this allow for a deeper sense of immersion, because the player is living the games’ events as an active participant rather than watching them happen as a spectator, it also allows games to directly ask questions of the player (this specifically I find very interesting, but it’ll be a topic for another day).

With this short preamble out of the way, I’d like to share that I had a borderline magical moment while playing SKALD: Against the Black Priory. It was a bittersweet moment, a harrowing and painful event masquerading as beauty and peace. I got so immersed in the story that I understood perfectly what my characters must have been feeling. I experienced a masterfully executed moment of Narrative Respite.

An Overview of SKALD

SKALD is an old-school RPG with party based turn combat which focuses heavily on narrative. Gameplay wise, in the overworld layer, you’ll be reading a lot of text, selecting dialogue options, rolling for outcomes depending on your characters’ skills, going on quests for NPCs - classic RPG goodness. On the combat layer, your characters have limited movement on a square grid, abilities that vary heavily between classes, different weapon and damage types, and status effects that they can inflict (or suffer).

It all feels extremely D&D, which, in my eyes, is a good thing. As you gather party members and give them different skills on level up, you’ll naturally start strategizing on a broader level. Your team as a whole will have a game plan - you’ll want certain characters up front, buffs you’ll want to use as soon as combat starts, maybe a character or two that you’ll set up to the sides so that they can get gigantic backstab damage. The different classes always feel like they have at least some synergy together, which makes it so that the player always has meaningful options.

Even though I find the combat very well executed, and I could talk more about why I find it so, today I’m mostly interested in the narrative. The game is mainly concerned with telling a compelling story which captivates you from the start and makes you want to keep going forward to understand what the hell is happening in the cursed island of Idra. There’s major elements of intrigue and an all encompassing feeling of dread, delivered through a Lovecraftian style of horror.

SPOILERS AHEAD!

SKALD: Against the Black Priory is a game about an adventurer who sets out on a quest to find a nobleman’s missing daughter. As we set sails towards the faraway island of Idra, things immediately start spiraling out of control.

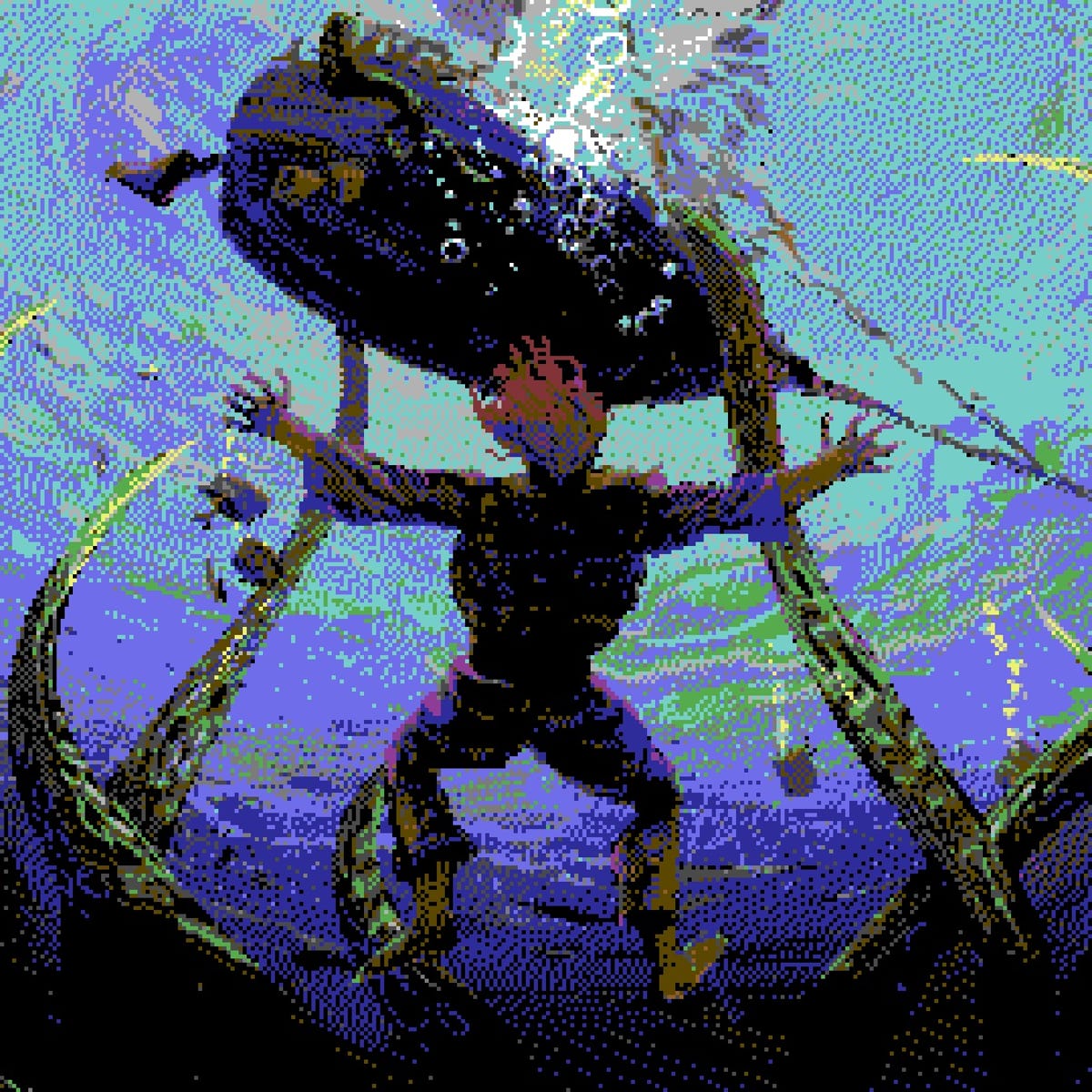

The game starts during a mutiny. The mercenaries we have hired to help us look for Embla, the missing woman, threaten to massacre the ship’s crew. The captain desperately pleads with you, telling you there’s too many bad omens to venture further into the seas. We have the choice of siding with either group. I try to avoid any bloodshed by using diplomacy, since my character is a noble cleric - and then, our ship is viciously attacked by a tentacled monster.

As we drag ourselves towards the shore, barely surviving the encounter, we start to see the game’s overall tone. Everything is bleak and desperate. There’s something very odd happening in these islands, and nothing feels quite right. Still, we trudge forward, moving ever so slowly towards our goal.

One of the first moments that really made this game stand out to me was a small side quest in which we help a crying mother retrieve her children’s bodies from a well. Apparently, they fell in, and she needs to bury them in order to feel at peace. When we drop down into the well, the water and walls are described as almost alien-like, and there’s something calling to us, an intruder trying to break into our minds. These children didn’t really fall in accidentally - they were lured here by this same intruder. We gather the children’s remains and, just as we’re about to climb the rope back to the surface, their two small ghosts attack us, trying to get us to stay here with them. When we finally get out, the mother stops weeping and thanks us, but feels… empty, off, like a ghostly reflection of what never really was.

This is what the main experience of the game feels like at the start. There’s always something weird going on, people aren’t quite themselves. There’s senseless violence which results in the misery of many who are forced to fight tooth and nail to hold on to their lives. For some reason, we seem to be somewhat unaffected, and we act as a sort of beacon for the natives of these islands. We’re the only ones who are able to survive and move past the violence, and so we’re relied upon to bring about some modicum of hope. And yet, whenever we succeed, it always feels like nothing is ever fixed.

At some point, you reach a camp of survivors who have taken refuge in a modest farmstead. You learn that these are the residents of Horryn, a large port where you were first instructed to go. It turns out that the madness has also touched this place, turning many once honest villagers into bloodthirsty cultists who massacred most of the population. The people you meet are the traumatized remainder of a once peaceful town.

You’re tasked with taking back Horryn. If you do nothing, the refugees will die. They’re vulnerable out in the open, but the cities’ walls provide, at the very least, some protection. The people are too sick, injured, and hungry to fight, so you’ll have to go with your party and no one else.

Getting to Horryn is harrowing, to say the least. The fields in the overworld are sprinkled with impaled, rotting corpses. The gates are not only locked, but stacked with desperate villagers who trampled one another trying to escape the violence. The town square is littered with dismembered remains, the cobblestone taking on the red tint of dried blood. As you look for an entrance, an emaciated villager implores you to find his wife. Fortunately, you do find her quite quickly, but -

Well - I don’t want to go into more detail about the game’s quests and story than is necessary. I’ve probably already shared way more than I wanted to. The point I want to get across here is that this game’s narrative is dark and unsettling, the mood grim and desperate. I cannot recommend enough that you experience it yourself, as my recap will always be vastly inferior to what the actual game can provide you. Seriously, the game is great. If you’re into RPGs, you won’t regret it.

A Haunting Peace

After you finally take back Horryn, you have a small moment to prepare yourself before embarking towards the heart of this madness. At this point, the game masterfully starts to set up the magical moment of Narrative Respite I mentioned at the start. A townswoman will ask you to pass by the town of Firgol, which is on the way towards your real destination. She mentions she was bound to visit her sister before all of the game’s events. She thinks that, if her sister is still alive amidst this chaos, she must be worried sick, and setting her mind at ease would be a great kindness.

You finish making your preparations, talking to relevant NPCs, getting some more quests, and gathering supplies. You sail north. Carefully staying near the shore so that another sea monster can’t get to you, you finally reach another stretch of land. A little house marks a village - what horrors await your arrival?

It’s Firgol. And, to your surprise, everything is peaceful and beautiful. The dialogue which describes your entrance to this town stands out because of how contrary it is to everything you’ve been experiencing up to that point. Even one of your party members, a pragmatic and often quite ruthless mercenary, seems to be shedding a tear at the sight of families and children playing so carefreely. In the midst of this tragic, seemingly world shattering event, there’s this little spot of the world that remains unblighted by the darkness that has seeped into every crevice of these lands.

Nobody in this town even knows what’s happening in the rest of the island. You sound like a raving madman whenever you describe what’s happening out there. Opposed to the lightheartedness and tranquility that’s felt in this town, it just seems like something so cruel and dark couldn’t possibly ever happen. For a moment, as a player you feel this way, too.

You eventually find the-woman-from-Horryn’s sister. She’s excited because she awaits her arrival. You explain to her what’s going on, and that her sister is safe, and she just… doesn’t believe you. How could she? Look at how normal everything is! Why would she take the word of a stranger claiming the island is under siege by unspeakable horrors? At best, it’s got to be some sort of sick joke, right?

There’s an event in Firgol called the “Carnivale”, and you’ve arrived just before it happens. It is a night of celebration, where nobility and peasantry forgo status in order to eat and drink together. The baroness tasks you with helping some of the townsfolk in preparing for the big night, and invites you to stay to have a sorely needed night of fun. Members of your party chime in, begging you to stay.

What follows is a series of very small and simple side quests. They feel completely trivial and insignificant compared to what you’ve been through up to this point. You help a baker gather some honey, a painter connect with her love interest, and a brewer dig out some mole burrows from an orchard. This is the sort of stuff that a traditional RPG would start you off with, before the adventure actually starts.

During these small sidequests, you get some hints that everything might not be as perfect as it seems. For instance, while gathering honey, some bees will try to sting you. Everyone knows that Firgol bees don’t sting - and yet, the beekeeper’s face is swollen and red. Then, while digging out the mole burrows, you see a creepy pair of eyes staring back at you, which spooks your character a bit. Finally, when helping the painter’s lover compose a song for her, you suddenly know the lyrics to a song you’ve never heard, and can only ever remember the last words of a stanza. Compared to the previous events, this is literally nothing, and it’s easy to understand why your characters feel a bit of denial. After everything they’ve been through, even insignificant things would surely make anyone anxious. You yourself might even be feeling it, too.

It’s finally time for the Carnivale. You eat, dance, and drink. The baroness has a surprise planned - a play in which the baron will play the lead role. You take your place in a moment that feels unexpectedly kind, where you can decide which party member you’ll sit next to. I, of course, sat next to the mercenary who almost wept at the sight of families, since I thought he’d be uncomfortable in this setting. For the first time he offered me a smile, explaining that he didn’t really like crowds all that much.

The play starts. The masked baron comes out, doing a silly but captivating voice. The townsfolk absolutely love it, and talk among themselves about the performance.

As a player, you’re conflicted. There’s this horrible feeling that this is all building up to something. But, of course, you want to believe that that’s not the case. Whatever you think will happen next, you yearn for the seeming innocence of this place to remain intact. You just want for this play to be over and for everyone to go on with their lives, blissfully ignorant of what horrors lurk this island.

The masked baron starts orating without making any noise. Something terrible is about to happen -

It’s here. What you knew was coming is finally here, even though you tried your hardest to deny it to yourself. Scattered corpses lay about, crazed villagers walk up to murder you. After a brisk fight, you walk into the castle to settle whatever the hell just happened. You find yourself confronting a disturbing image.

The children of the village have been placed in an odd, ritualistic circle. They’re unconscious. Over them stands the baroness, talking to herself. As you interject, she draws a dagger and walks towards the children, lashing out about not having any kids of her own. At this point you intercede and kill her.

With the children saved, you walk up towards the throne room. You expect a tough fight from whatever monster did this to this quaint, peaceful town. You only find the baron’s corpse, however. Who knows how long he had been dead, or if he had been supplanted by the ethereal monstrosity that brought about this darkness.

Once again, you’ve succeeded, but nothing was really fixed. You’re left wondering if this town would’ve done better if you hadn’t ever showed up. The levity and beauty of this place now seems impossible and foreign. Were you the one to destroy it? Alternatively - did it ever really exist?

Narrative Respite

The reason I found this sequence so magical, other than the complicated tapestry of feelings, is because it is a brilliant mix of great narrative pacing and smart mechanical choices. This moment of Narrative Respite, a moment of levity and tranquility amidst ever increasing stakes, allows the player to settle on brighter emotions and connect with the game in a more complete and interesting way.

Traditional RPGs tend to put the inane and unimportant quests at the start of your journey, right before the adventure starts. It’s a way of easing you into the story, allowing you to safely interact with the setting at a slower pace. Here, it acts as a breakpoint which puts the earlier events into perspective. After entering Firgol and doing silly little fetch quests for kind strangers, the misery and suffering you’ve witnessed feels a million times worse - so much so that it almost seems impossible.

This moment of brightness also adds some much welcomed levity into the story. Up to now, you’ve only met your party members as warriors in moments of stress and danger. Here, you can meet them as people, and bond with them over insignificant things. As a consequence, you care about them as characters much more.

What I like most is that this moment plays tricks on your mind, much like the Lovecraftian themes this game goes for. There’s always this nagging doubt in the back of your head that such peace and beauty can’t exist in a world like this. Even though you’re seeing it with your own eyes, it must be an illusion, a place which could only exist in the confines of your imagination. Like an oasis in a desert, the apparent mundanity of this town is exactly what makes it suspicious.

At the end of the day, you’re right to doubt the peace of this place. Just as any other place on this island, there is something wicked lurking in the shadows. And yet, you almost feel guilty doubting it, like if your disbelief was somehow insulting to this town’s innocence. This feeling of appreciation for the peace amidst the chaos is also the reason the final reveal feels all the more gut wrenching and impactful.

Narrative design is a huge part of game design. Moreso in some genres than others, of course, but it is an essential part of what allows our players to get emotionally invested in our games. The feeling of agency, of having our actions matter, is one of the things I find most fulfilling in games. Even though I was predestined to fail, and I couldn’t have ever saved Firgol, the fact that I couldn’t prevent its destruction stings all the same.

I usually like ending these on some conclusions, some insight or concrete piece of knowledge I can pull from my analysis. In this case, I think mostly we can learn from adding levity to games. Other, more professional game designers talk about this as having quiet parts in between your big moments. If you keep the pace too high, then all of the action or drama starts to lose a bit of meaning, and players can become desensitized to the story you’re trying to tell.

I don’t think that’s the only reason this moment is so successful. Simply put, it’s brilliantly written, and it interacts beautifully with the game’s setting and lore. It reaches out from the screen and pulls you in as a participant in the game’s emotional tone. There’s no amount of praise I can give it that can even express what playing it yourself feels like. I can’t recommend SKALD enough!