KOTOR and Diegetic Morality

The possible pros and cons of making morality an in-universe game system

An Introduction

Hey, everyone! This is Dissecting Game Design, a publication where I discuss videogames and attempt to focus on specific game design aspects I find interesting and worth discussing. I am not an expert on game design by any means, so take my opinion as just that - an opinion. This is by no means a review. Even if it were, I think reviews should be about engaging with art through different perspectives instead of attempting to assign a concrete value on it. Please approach this as a discussion in which I try to figure out why I think something works (or doesn’t work) from my subjective game design perspective.

Morality in Games - Two Very Different Approaches

Today, in the first part of a two part series, I’d like to discuss morality in games, and how different approaches towards it lead to distinct player experiences. While there’s a million different variables, such as the quality of writing or the story itself, I’ll be focusing mainly on whether the presented morality system is diegetic or non-diegetic, since I find this difference has the most impact when making design decisions. To do so, I’ll take a closer look at two (very different) games which’ll act as representatives of their respective morality system.

Before we start - a diegetic morality system, according to me, is one where morality is embedded in some mechanical way into the game’s universe. Put another way, there’s in-universe consequences, be they narrative or mechanical, to acting morally or immorally when given a meaningful choice between the two. Games like GTA don’t count - even though going on an immoral civilian killing spree has the mechanical consequence of getting the cops involved, there’s no real, comparable, and meaningful way of acting morally to balance it out.

My first contender, and the one I’ll be examining in today’s post, is Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, or KOTOR, as it’s lovingly called by fans. It’s an RPG with a heavy emphasis on story and branching narrative. Much like its source material, there’s lots and lots of choices to be made between the light and dark side - a perfect fit for a diegetic morality system in a game. Your character can either be a noble Jedi warrior or a ruthless Sith lord, which has a direct consequence on mechanical and narrative elements.

What’s KOTOR about?

KOTOR is a widely beloved RPG game in which the player guides the story by making tons of choices that are labelled good or bad, as the light and dark side respectively. These options are mostly presented during dialogue sequences, where the player is able to influence the events of the story by making choices.

The very broad and overly summarized story of KOTOR (spoilers!) is that you’re a powerful Jedi who’s attempting to stop Darth Malak, a Sith lord who’s harnessing ancient technology in order to wipe out the Republic.

Set in the aftermath of the Mandalorian Wars, a brutal conflict that tore the galaxy and the Jedi Council apart, you start off as a seemingly regular soldier who then starts to figure out they’re keenly sensitive to the force. Along the way you gather interesting party members, including Bastila, a snarky and self-important Jedi who eventually gets you into training with the Council. You learn suspiciously quick and attain the rank of Padawan after crafting your first lightsaber.

After this, you’re tasked with retracing Malak’s steps in order to find the legendary Starforge, a gigantic shipyard capable of assembling the most powerful army of all time. You’ll be visiting four different planets with their own self contained quests, all of which end with you visiting a Star Map. Each of these artifacts hold a clue to the Star Forge’s location.

Eventually, you find out your true backstory. It turns out that you were once Darth Revan, Malak’s master, but your memory was wiped by the Jedi Council in order to try and get you to turn to the light side once again. Your actions up to this point kind of determine whether that gamble worked or not - you’re now either a soldier of the light, or a follower of darkness.

After finally gathering all the pieces, you get to the Star Forge, which Malak has captured. You defeat him in a climactic final battle, as master and apprentice are pitted against one another for the last time. Here, the story culminates with either you destroying it if you chose the path of the Jedi, or with you capturing it for your own uses as a Sith lord.

In a more mechanical sense, KOTOR is an RPG game with lots of dialogue and turn-based combat. During most of the game you’ll be talking to different NPCs, taking on side quests for them, and making choices that will influence your moral standing. Even though some characters have very definite affiliations of their own, there’s always a way to play off them to gain light or dark side points.

In terms of combat, when you enter a fight, the game will pause and allow you to queue up different abilities. After a determined amount of time, every character will execute whatever action is next in their queue. Some of the options you have available to you include attacks with your weapon, unleashing defensive or offensive force powers, and using consumables such as grenades or first aid kits. The combat isn’t super complicated, but there’s a nice sense of balance to all of the options.

Additionally, you can pick a class both at the start of the game and when you first become a Jedi. Some classes are more combat oriented while others make better use of skills and force powers, giving you some more meaningful choices to make in regards to building your character. When I was younger I used to love building lightsaber-based characters to shred whatever was foolish enough to stand in my way, but nowadays I enjoy playing more control-oriented and force-driven characters.

Mechanics of Morality

The moral choices that make up a core part of the KOTOR experience permeate the entire game, be it in large plot points or minor side quests. They vary hugely in importance - you can gain dark side points by being snarky to somebody, or by deciding to indulge in genocide. You get more dark side points for the latter, obviously, but the point here is that there’s plenty of opportunities to make decisions.

The points you gather act on a single sort of “gauge” system. You start at a middle point, which we’ll call 0. The light side is represented by a 100 while the dark side is represented by -100. Any points you gain are added to this single gauge, meaning that if you’re already close to the light side, and then gain dark side points, they’ll be “subtracted” from your current affiliation. In other words, you’re functionally either on the light side or dark side.

When you max out your gauge at either side, you gain access to bonuses, such as additional stats based on your character’s class. Additionally, there are some force powers that are outright restricted to an affiliation, and many that often get more powerful and easier to use the deeper you are into their respective side. This means that the player is always incentivized to pick either alignment for a playthrough and stick to it.

While in a more complex view of morality a player might want to make a decision depending on a situation, this system means that you’re often choosing based on what you think the result will be, maximizing for your chosen side. For example, if you’re playing light side, then you often just pick the nicest, most inoffensive options possible. By doing so, you’ll have access to better force powers, additional stat bonuses, and the respective storyline decisions later down the line.

So what’s the result?

Overall, this system results in morality being reduced to a playthrough decision. Moral dilemmas aren’t really dilemmas per se - you just pick whatever will make your character more aligned with the side you’ve chosen for the current playthrough.

This works fine from a mechanical perspective - there’s a constant sense of progression as you engage with the main and side stories the game has to offer. Whether it be small or big decisions, you’re always working towards a goal, granting you access to more powerful abilities and such. This results in a satisfying feedback loop in which you’re rewarded for playing along with the game’s role playing aspects. You can feel yourself becoming stronger the more you align yourself with one of the two sides.

In a more meta progression sort of way, it also means that the game has double replayability. With essentially two different stories to play through, and some variations in between, it makes sense to roleplay as an ambassador for both sides of the force. It also increases the amount of ways you can engage with the character building aspect of the RPG.

Narratively, however, I think the story tends to suffer a bit because of this reduction of morality to a dichotomy. The game offers a very vast and interesting lore, as well as more nuanced takes on the Jedi and the Sith that differ to what the movies offer. I’m not the most knowledgeable Star Wars fan out there, far from it, but here’s my opinion anyway - take it with a grain of salt.

Traditionally, the Jedi are selfless and noble. They devote their lives to becoming vessels for the universe and the force, abandoning all earthly passions and mundane feelings. The more detached a Jedi is from the human experience, the better they are at bringing about the will of the light side of the force.

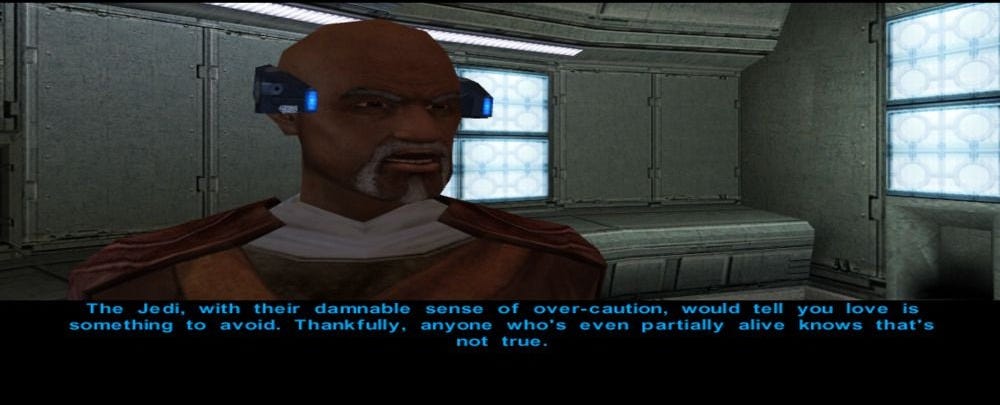

However, KOTOR shows us another side of what their ideas can bring about. In this case, they can also be arrogant, passive, ineffective, and excessively bound by traditions. Abandoning human feelings and seeing everything through the invisible and often incomprehensible will of the force also makes them unempathetic and even capable of seeing mass civilian death as just a natural consequence of the universe’s expression.

The game’s events are preceded by the Mandalorian Wars, as I mentioned above. At a time where a ruthless and war-mongering civilization invaded the Republic, many finding their homes colonized or destroyed, their families lost or slaughtered, the Jedi Council refused to take any action whatsoever, citing that it wasn’t yet time to intervene. They were ostensibly waiting for a signal from the force.

This is what prompted Revan and Malak to break off from the Jedi. When confronted with the death of countless people and the systemic inaction of the Council, they saw fit to lead other Jedi into the fray. Eventually, their efforts turned everything around (even if it turned them to the dark side), and the Republic won the war.

The Sith, on the other hand, aren’t presented as only evil and bloodthirsty, even though they very often are. Embedded in their code and dialogue, there are themes of personal freedom, of self-growth, of living through action and embracing passion. There’s also commentary on how this overly individualistic approach can result in outright unempathetic people. Even worse, these guys feed off hatred to fuel their powers.

I like this game’s rendition of the Sith. They aren’t only evil because they enjoy being evil - there’s often a background of trauma and pain, balanced with an adherence to the ideals of striving for conflict (or change) to better one’s self. They believe that passion is inherent to life, and that it is through our embracement of such feelings that we gain the power and courage to act upon our will in order to change the world around us.

Even though both the Jedi and the Sith hold commendable ideals in their own ways, it is also clear that they represent a perversion and corruption of them. While the Jedi don’t want to change anything for the better because of an adherence to the status quo and an aversion to conflict, the Sith don’t want to because they’re obsessed with power, hatred, and self-gain. Neither of these options seem like an effective agent for good - leaving me, as a player, with the desire to be somewhere in the middle, such as a Jedi with more individuality or a less self-serving Sith.

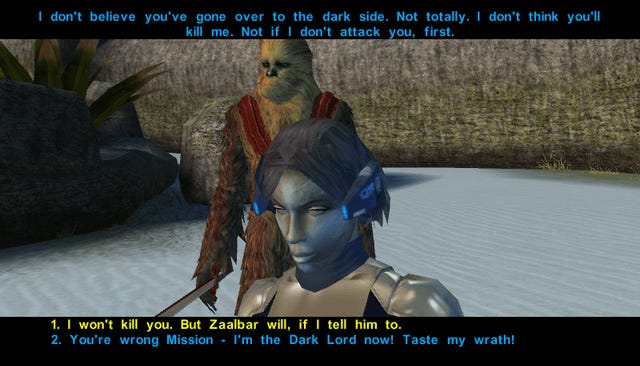

So what choices do we actually get when we want to side with either the light or the dark side? Well, often, they’re just very caricatured versions of good and evil dynamics. If you want to be good, then you have to be obscenely good. You will give away most of what you have, make things harder on yourself, and look for other’s redemption even when you know they’re far too gone (although I do like an aspect of this - it’s often harder to be good than it is to be evil). And if you’re evil, then you’ll be absurdly evil. You will kill people for the fun of it, you will revel in violence, you will always choose to maximize harm.

By reducing morality to a dichotomy, there’s very little room left for nuance. You’re either a martyr or a war criminal. You will either make a peace deal with an alien race or wipe them all out for some extra credits. You will either go into the endgame with a party full of loving friends as a saint, or you will have forced them to turn on one another with lethal consequences. What is there left of the commentary on the arrogant and ineffective ways of the Jedi? In what ways do you embrace the self-betterment mindset of the Sith? It feels like these interesting takes can be a bit of lost potential when your choices don’t reflect that same nuance.

Don’t get me wrong - I love both stories KOTOR has to offer. Side quests end in satisfying ways, characters grow to love you or hate you, you make decisions that seem natural based on the role you’ve chosen. You feel like you have lots of agency, like your choices really do matter, and like, ultimately, the fate of the galaxy rests on your shoulders.

What I’m critiquing is more the end result of codifying morality into a diegetic morality system. Because of the design incentives of making characters more powerful the more they align with a particular side, there’s also narrative incentives to make characters progressively more cartoonishly good or evil. This, in turn, makes it so that there’s little room for more complex morals to be discussed.

In Conclusion

I think diegetic morality systems, just like any other design choice, have pros and cons. I like that they offer some more replayability, the fact that they offer you mechanical and tangible rewards to narrative choices, the fact that they give you some sort of power fantasy as you roleplay one of the two sides. However, I dislike that they can tend to narrow down the narrative into overly cartoonish depictions of good and evil, and can ultimately leave the player feeling that their choices weren’t really theirs. When you branch out the narrative into two distinct lines, it’s possible that a player will feel like they’re just being railroaded towards a conclusion, which holds the risk of making choices feel less meaningful, especially if said choices are so over the top that no one would consider them. Alternatively, it is possible that a player will feel the opposite effect, because their choices of good and evil shape the character and the world in a massive way, leading to two completely different outcomes for the universe at large.

I think KOTOR is wonderful, and there’s a reason why I’ve continued to replay it over the years since I first touched the game. The narratives are obviously so satisfying and interesting that they have held people’s attention for over two decades. However, I think it’s good for developers to examine how or why they implement morality into their games. Diegetic systems might be a good fit for our game, or they might not be. To make the best choice, I think it’s best to think about the implications of choosing one or the other both in terms of player experience and incentives for us as developers.

In this case, I think it’s important to keep in mind that diegetic moral systems, like most other game systems, attempt to incentivize and reward player behavior. However, morality in the real world doesn’t work this way. While we can enjoy a much brighter life by being good people - and we should be relentless in our efforts to become better -, there’s no experience gains, no level up, no cash prize. Mostly, we have internalized feelings on whether what we did was right - and that’s about it. By codifying morality into game systems in this way, I think we understandably sacrifice a lot of nuance and depth. I don’t think any game can account for and reward the countless moral choices a person might make in any given situation. And this can be completely okay - it’s just something we have to be mindful of when developing games.